In 2021 Genevieve Kingston published an essay in New York Times titled “She Put Her Unspent Love in a Cardboard Box.” It tells the story of her terminally ill mother leaving a cardboard chest of letters and gifts for Kingston and her brother to be opened after her passing. The essay gave birth to Kingston’s memoir DID I EVER TELL YOU? released this Spring.

In 2021 Genevieve Kingston published an essay in New York Times titled “She Put Her Unspent Love in a Cardboard Box.” It tells the story of her terminally ill mother leaving a cardboard chest of letters and gifts for Kingston and her brother to be opened after her passing. The essay gave birth to Kingston’s memoir DID I EVER TELL YOU? released this Spring.

Kingston’s memoir journeys beyond the mere recounting of grief, exploring themes of parenthood, relationships, and mental health. Through her poignant narrative, readers are not only exposed to the rawness of loss but also to the enduring strength of love.

In a sincere and intimate interview, Kingston revealed to me that this book serves as her dialogue with her late mother’s letters and messages. “It became my way for responding to her,” she explained. Kingston opened about shaping the book, and we delved into the intricate connection between writing and the journey of healing. This video interview was edited for clarity.

Britta Stromeyer: You used the essay to map the structure of the book. Can you tell me more about this?

Genevieve Kingston: What became clear to me is that the frame was really important. Often people love to ask, “Why now? Why do you need to write about this right now?” For me, that frame was crucial. I was writing at a time when I had come to the end of the birthday gifts my mom had prepared, which stopped at 30. Left were three boxes titled Engagement, Marriage, and Baby. It felt like a moment of personal reckoning. In my early 30s, I was thinking about the shape of my life and what path to choose going forward.

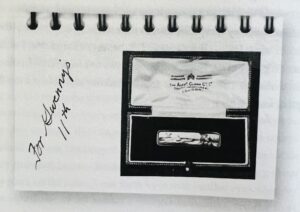

At the beginning of the book, I refer to the three remaining boxes before traveling back in time. The story then moves chronologically. The progression of opening the boxes is part of the structure, highlighting different moments where my mom miraculously anticipated what I might need at a certain age. For example, the letter for my first period was invaluable. It wasn’t easy for me to talk about that with my dad, so being able to read her advice about boys, romance, my changing body, and belonging to a community of women was incredibly helpful. She even included a pack of pads—she thought of everything.

However, there were also times when there wasn’t a letter or box for situations my mother couldn’t have anticipated. For instance, ten years after she passed, there was another traumatic event that I write about in the book when I felt her absence deeply. These moments were equally important in shaping the story and assigning meaning to it.

In both my essay and book, I arrived at the same conclusion: the unwavering belief that love is stronger than death.

BS: You cannot help but marvel at your mother’s love, foresight, and courage in putting this together. As you approach the age your mother was when she was diagnosed, what does that mean to you? Does this change your perspective when reflecting on your younger self? Is your understanding ever-evolving, or do you feel some sense of closure?

GK: Great question! As I get older, my awe increases. When I was younger, I assumed parents were capable of extraordinary things and thought anyone would have done the same in that circumstance. But now, it’s truly different to empathize with what she must have experienced, knowing she had to leave us behind and that her life was being cut short. I can’t believe she pulled this off. She executed this enormously emotionally challenging task. Considering her perspective, I find myself grieving all over again, thinking about what it must have felt like for her. My view on this is ever-evolving. There is also anxiety surrounding the notion of outliving the age at which my mother passed away, which may be common among others who’ve lost their parents early.

“I would have told her I felt guiltiest of all that part of me wanted this to finally be over, so I could begin to remember her the way she used to be, instead of the way she was now.”

BS: I find your treatment of “time” in this book intriguing. Young Gwen’s desire to stay rooted in the present is driven by the fear of a future without a mother. There’s a powerful moment in the book toward the end of your mother’s life when you recall a conversation with your father, who asks if there is anything you’d like to say to your mother before she dies. You ponder the things you feel guilty about and later ask your mother if she feels guilty about anything, wishing and hoping she’d ask you the right questions to guide you to your answers. You write: “I would have told her I felt guiltiest of all that part of me wanted this to finally be over, so I could begin to remember her the way she used to be, instead of the way she was now.” Until then the thread is centered around not wanting to enter the future. And here you find yourself of wanting to make that step, you had been resisting and fearing up until that moment. Can you talk a little about that?

GK: Wow, that’s so insightful. There are two things going on there. One is the issue of guilt. I believe guilt and shame in children are fascinating topics. As kids, we often assume we have much more control than we do. We feel our thoughts can make things happen or prevent things from materializing. Young children have a rich interior life, but they often lack the words to articulate their feelings. In that moment you referenced, I didn’t say anything, but I had this yearning of, “Please, help me say how I feel because I don’t know how to express it yet.” My mom was so good at helping me express and process my feelings. By then, her cancer had progressed too far, and she was unable to do so.

There was a sensation of impatience and a lot of guilt around the idea that death might give me some relief. It’s not uncommon for people to feel guilty about the sadness of watching the slow process of a loved one changing and losing parts of themselves little by little. On the flip side, there was the gift of being able to prepare and have those conversations.

“Some nights, when my parents’ voices rose the loudest, I would leave my hiding place and walk out into the middle of their battleground. Standing between them, I would scream, or cry, or knock something over, anything I could think of to draw their attention away from each other and onto myself. It was safer for them to be angry with me, because I, at least, would always be forgiven.”

BS: Your pages are brimming with wisdom from your mother’s reflections on life, interspersed with what I’d like to refer to, if you allow me, as “Gwen-isms,” as you experience your parents’ marriage. You describe a moment in the book when you insert yourself into their fight. You write, “Some nights, when my parents’ voices rose the loudest, I would leave my hiding place and walk out into the middle of their battleground. Standing between them, I would scream, or cry, or knock something over, anything I could think of to draw their attention away from each other and onto myself. It was safer for them to be angry with me, because I, at least, would always be forgiven.” I was wondering if you can talk more about this.

BS: Your pages are brimming with wisdom from your mother’s reflections on life, interspersed with what I’d like to refer to, if you allow me, as “Gwen-isms,” as you experience your parents’ marriage. You describe a moment in the book when you insert yourself into their fight. You write, “Some nights, when my parents’ voices rose the loudest, I would leave my hiding place and walk out into the middle of their battleground. Standing between them, I would scream, or cry, or knock something over, anything I could think of to draw their attention away from each other and onto myself. It was safer for them to be angry with me, because I, at least, would always be forgiven.” I was wondering if you can talk more about this.

GK: It was one of those things I did instinctively without realizing why. It was a pattern my mom pointed out to me, and she decided early to seek out therapy when I was very young. She noticed her daughter was taking on the responsibility for ending parental fights by distracting them, acting out, or misbehaving. I worried they might leave each other. It felt safer knowing they would be mad at me because I knew they would never leave me.

BS: Kids are often smarter than we give them credit for. They may not be able to articulate why, but they’re more connected to their bodies in that way. Your memoir is nuanced and layered beyond the grieving process. It touches on parenting, coming of age, and mental health. You address not only your mental health struggles, but also those of others, and I am careful here not to spoil a plot point. You are very open in the book about your battle with homesickness, anxiety, and depression. As survivors of traumatic events, writers often engage in writing as a form of restoration, a way to help cope. Do you think that was the case for you?

GK: Writing this memoir was therapeutic, and so is acting for me. As a young person, acting allowed me to be myself. I could be emotional on stage in front of other people in ways that were socially acceptable and in ways my peers could manage. It was an opportunity to process grief through the characters’ experiences and through other writers’ words. I’ve always loved language, but it wasn’t until I was older that I really felt like I had anything to say or could access the kind of stories I yearned to tell. Writing this book was a joyful and informative process. I learned a great deal about my mom and myself. I do think I couldn’t have written it if I hadn’t been in therapy.

“It felt nice to go back and acknowledge that little girl and her feelings. From an adult perspective, I could reassure her and say, “It’s okay. You’re okay, and you’re going to be okay.”

BS: In your experience what do you think is the relationship between the memorialization of experiences and the craft of producing a narrative that connects with readers? Did you experience any tension between writing as a personal activity and publishing a text that is meant to be circulated? And did you approach it that way?

GK: I think the first draft can be for yourself. It’s a generative process—laying all your cards on the table. Then, you comb through, refine, contract, or expand to shape it. A memoir can encompass various spans of life; mine spans over thirty years. I had to be rigorous with myself and cut anything that didn’t serve the particular story I set out to tell. An interesting anecdote from college might be a great tale, but if it didn’t serve the theme, character development, or plot, it had to go. You write a first draft for yourself. But by the time you’re asking for people’s time and attention, you have to consider the reader’s experience. What do I want to communicate in this precious time we have together while you’re reading my book? What do I hope you get from it?

BS: In the beginning pages, you are still very young. There are many moments where the reader experiences five-year-old Gwenny. How were you able to access that child’s point of view? I imagine it must have been very emotional for you.

BS: In the beginning pages, you are still very young. There are many moments where the reader experiences five-year-old Gwenny. How were you able to access that child’s point of view? I imagine it must have been very emotional for you.

GK: This part was quite therapeutic for me. It was nice to revisit that time in my life; it was healing. I would start with an image or fragment. It was helpful for me to remember conversations I’ve had with my therapist, as I’ve been in therapy since I was about six years old, and encouraged me to articulate how I felt. During the writing process, a particular event might come back to me, and I might struggle to remember how I felt in that moment. But exploring questions like my therapists used to ask me, “How does this feel in your body? What are you most afraid of? How does it feel when your mom goes away?” was helpful and allowed me to label these experiences viscerally. It felt nice to go back and acknowledge that little girl and her feelings. From an adult perspective, I could reassure her and say, “It’s okay. You’re okay, and you’re going to be okay.”

BS: I would like to ask you about is the title. I don’t think I am spoiling too much by revealing that this phrase makes an appearance in the book. How did the title come about?

GK: I’ll be honest with you; I really hate titles. I’m not good with them, and I did not come up with this one. My wonderful agent, Brettne Bloom, plucked out that phrase from a scene and said, “I think this is it.” What I love about it is that it captures how we keep people alive through their stories. With each new piece of information about my mom, it felt like getting extra time with her. And the other part is my response to her with this book. It was a way of responding and telling her, “Here’s what happened since you’ve been gone. Here’s my side of the story.”

“In every section, and almost every chapter, we reveal a package that is thematically connected to the events of that section and my life.”

BS: You’re also a playwright and an actor. How has playwriting informed your crafting of this memoir and vice versa?

GK: Interesting question. You might notice that the book has a three-act structure. It’s something I am comfortable with, so I thought, “let’s try it.” Dialogue also plays an important role in the book. I had to really trust my instinct for scene and setting. This is partly why the chapters are quite short, especially in the first part. These are early childhood memories and have a snapshot quality to them, like vignettes, which I borrowed from playwriting.

The other part of the narrative is driven by the act of opening these boxes. In every section, and almost every chapter, we reveal a package that is thematically connected to the events of that section and my life. These reveals happen at different moments within the chapters, but I believe there’s one in each chapter. This action felt quite theatrical to me. These reveals help to drive the plot forward and, hopefully, keep the reader’s attention.

The other part of the narrative is driven by the act of opening these boxes. In every section, and almost every chapter, we reveal a package that is thematically connected to the events of that section and my life. These reveals happen at different moments within the chapters, but I believe there’s one in each chapter. This action felt quite theatrical to me. These reveals help to drive the plot forward and, hopefully, keep the reader’s attention.

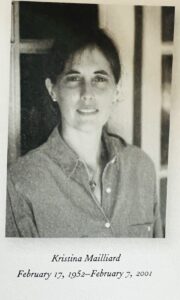

Additionally, the placement of photographs felt theatrical as well. They create pauses that enhance the storytelling. You pause where you place the photographs in the text, and it influences the rhythm through which the reader experiences the story. I hadn’t thought much about this until now, but I’m currently writing my first play since I wrote the book. I’m not sure if writing the book has influenced how I’m writing this play differently. I’ll have to keep thinking about that as I continue.

BS: What is the most useful writing advice you have received?

GK: I think it’s easy to assume that people get bored when there isn’t enough going on. However, I feel readers get bored first if they’re confused. Clarity is important. In my writing, I gravitate toward complexity, moving back and forth between different storylines and timelines. There is a temptation to overcomplicate the structure. For this book, I had to trust that it would be enough to tell the story mostly in chronological order. I believed that this approach would successfully take people on this journey and make them feel like they were growing up with me. Simplicity and clarity first—that’s the lesson I learned.

“The real gift now, not being in that space, is experiencing times in my life when I can forget about the future and be in the moment.”

BS: Your childhood was consumed with the idea of life and death. Has your perspective shifted since then, especially during the process of writing this book? Also, let me combine this with another question regarding your relationship to time we talked about earlier. How do you feel about the future now? Are you looking forward to tomorrow? Is there a difference in how you perceive it, or are you still focused on staying in the present moment, resisting what’s coming next?

GK: During the writing process, I suddenly became preoccupied with my own death in a way I hadn’t been before. I don’t want to sound arrogant or imply that this undertaking was important to anyone but me, but I really, really wanted to finish this book. I developed an irrational fear that I would die before completing it. This fear was so intense that I became scared of flying, which had never bothered me before. But as soon as I finished the book, that fear disappeared. I felt a sense of relief and accomplishment, knowing I had told the story I wanted to tell and shared my mom’s story in this way.

Since my early 20s, I’ve come to appreciate the gift of being able to forget about time. As a child, I was always preoccupied with not wanting the future to come, which ironically kept me focused on it, even negatively. One of the hardest aspects of a long or terminal illness is that you can’t forget about time. You feel pressure not to waste it. The real gift now, not being in that space, is experiencing times in my life when I can forget about the future and be in the moment. Not knowing what will happen a year or ten years from now can be wonderful, especially if you’ve had times when all you could think about was the future. It’s such a gift to live without that worry.

DID I EVER TELL YOU? is available now and was optioned for translation into eleven languages and set to be released in sixteen countries later this year including my birthplace Germany.![]()